Contents of Post

Hey everyone! For those of you who were expecting a blog post from Jenson this week – surprise! My name is Faith Donovan, and Jenson is one of my old friends from back in high school. I’m from Alberta, so naturally he has asked me to whip up a few words about travel experiences around here. Seeing as he is all the way over in Vienna. Luckily, my husband, Sam, and I recently spent a day in the beautiful town of Drumheller, Alberta. While there, we visited the Atlas Coal Mine. Therefore, I have the honour of sharing our experience! Let’s get into it.

Drumheller

Drumheller is in the badlands of south-eastern Alberta, located in what is colloquially known as Dinosaur Valley. However, the impressive bones and fossils that we find in abundance throughout the area were not the original intent of the small, booming town in the early 1900s. Not very surprisingly, they quickly discovered that the different coloured strips of dirt in the valley were actually huge veins of coal. Therefore, it didn’t take long before they opened the first coal mine in 1911. This became vitally important as we entered into World War I. At the height of the coal boom, there were over 130 active mines in the valley. Yet, none were quite as impressive as Atlas Coal Mine.

The Atlas Coal Mine

One of the neat things we got to see on our trip was the Historic Site of the Atlas Coal Mine. Even though I’ve lived my entire life in Alberta, I had actually never done the tours at this location. Therefore, Sam made sure that we saw it this time. It’s located about 15 minutes outside of Drumheller and is home to the last wooden tipple in the country. Not only that, but it’s also the largest tipple in North America.

A tipple is what they would use as a long chute to move the coal. It would take it from the mine down to where it could be loaded into the trains. The main intent of the coal mined here was for heating homes, cooking, and the generation of electricity for the war era. It was known as one of the safest and most efficient mines operating.

Throughout Atlas Coal Mine No. 3’s 40 years of activity, only thirteen people died in tragic accidents. These were mostly through failing equipment and a couple of explosions. Even though it was considered relatively safe. This was due to the flat-lying seams and therefore low levels of methane gas as a result. People from all over the world came to work here, as it was a reliable source of income. As the mining town was just across the river, they could go home to their families at the end of the work day.

Tours At The Atlas Coal Mine

We went on two different tours that day. The first was on an electric battery-powered coal train from 1936 that was originally used in the mine.

We sat in the carts as we toured around the site. We quickly realized that the maximum height of the mine was only about 4 feet tall. As a result, most of the workers were under 5’2”. This was to reduce the strain on their backs from bending over all day. Even children as young as 9 were taught to stand near the cart tracks with lights! That allowed the workers to see where they were going.

Unfortunately, they weren’t the only innocent souls working the mines. They also had what they called “pit ponies”. These are ponies that would spend their entire lives inside the mine. They would help move large pieces of equipment or pull tons of coal. They were so used to the dark that if they ever had to leave the mine, people had to wrap a cloth around their eyes. Why? So that they wouldn’t go blind from the sudden light of the sun. Older children who worked the mine for some time were eventually trusted with their own pit pony. They were responsible for keeping them in good health and ultimately becoming best friends with a lot of them.

Reopening Of The Mine As A Historic Site

At the end of its life in 1979, the mine was closed as we moved from coal to natural gas. The mine entrance was exploded shut, locking away hundreds of miles of veins cut out into the small mountain. Of course, this was done for the safety of curious spelunkers. As mines can be very dangerous even at the best of times. But after being abandoned, the pillars move and the walls weaken, allowing for a collapse at any time.

It wasn’t until 1989 that it became a National Historic Site. When one of the original miners decided it was important to preserve its history. As a result, the donations they receive from visitors go towards helping to restore the mine. Throughout recent years, more and more of the entrance has been excavated, allowing tours to walk inside the very beginning of the mine and experience what it would have been like to work in those conditions.

Second Tour

That was the second tour we did that day. We got to walk up inside the tipple where the original equipment still stood. Outside, we rounded the blacksmith cabin, where they had experienced a fire at one point and miraculously were able to save the building with the primitive fire extinguisher they had. The roof and some of the walls remain scorched to this day.

And then we walked up to the entrance of the mine. When Sam visited over eight years ago, he mentioned that all they were able to do was stand outside looking inside a small portion. When we went now, they had excavated enough space for over forty people to stand comfortably. It was damp, pitch black, and seeing the size of a mine cart inside the shaft only stood to serve the sheer size of what lay behind the fallen rubble.

At one point, they hit limestone, which is just nasty to work through. Besides, it was not profitable to spend time mining through it. As a result, Atlas Coal Mine No. 4 was started on the other side of the hill, working towards the centre to get the last remnants of coal that they could. At the end of the tour, we made our way back down the hill. From there, we could see this huge black slag pile on the side of the hill. It’s all the material left over from coal mining that was unusable and back then, there were no environmental laws saying you couldn’t just dump your waste and ignore it.

So that’s what they did. Our tour guide warned us never to step on it, as the friction from our shoes would set us on fire immediately and cause the pile to start burning indefinitely. The slag pit for the No. 4 mine has been on fire for over 20 years with no signs of stopping and remains to be an environmental hazard.

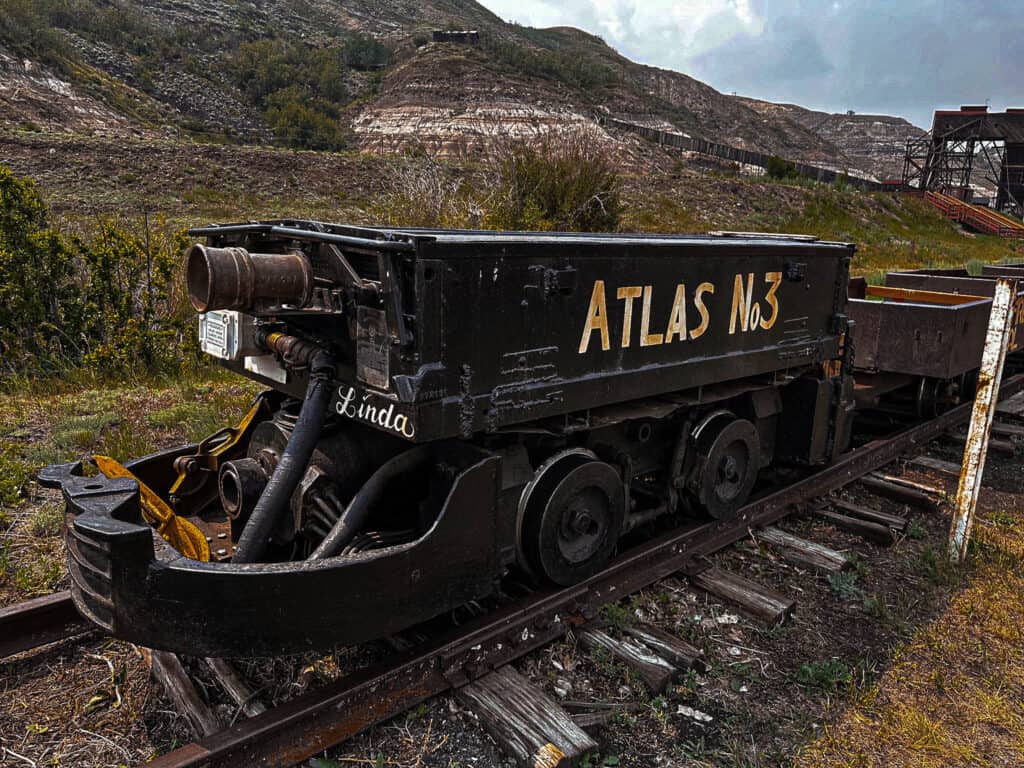

From there, the rest of the historic site still held the original bathhouse, lamp house, and mine office. We also observed the “mine cart graveyard” where they came to rest at the end of their lives and were never moved again. I found myself oddly saddened to see them slowly sinking into the earth, eventually being retaken by nature. But that is the beauty of it as well. We didn’t know at the time the devastating effects that opening coal mines would have, especially for workers who needed job security for their families. And though the remnants are still here to view after nearly forty years, life is in abundance all around it.

Final Thoughts

I think it is vitally important that we preserve what we can in order for adults and children alike to learn the history of our past. This way, we can make sure to create a future that is brighter, safer, and healthier for us and nature alike. If you ever happen to be in the area, make sure to set aside some time for the Atlas Coal Mine. I was certainly enriched by the stories shared and travelling somewhere I had never been before.

Anyway, I want to thank you for taking the time to read this personal history lesson that I was lucky enough to witness firsthand. I am grateful for Jenson asking me to share my experience and I want to challenge you to do the same. Even now, writing this over a month after visiting, I got to relive the day all over again. I think there is something beautiful about sharing stories and learning a little bit more about our beautiful world together. So until next time… Goodbye!